Summary

The crash of an aerial object outside the city of Roswell, New Mexico, in 1947 is perhaps the most well known alleged UAP event in the history of the phenomena. However, at the time of its occurrence, the Roswell crash generated little more than a brief stir of media attention.

The renown of the Roswell sprung up decades later when a handful of witnesses and UFO investigators began to allege that the 1947 crash left the wreckage of an extraterrestrial spaceship and its occupants in the hands of the U.S. Government, which had since perpetrated a massive cover up.

The U.S. Air Force, often cast as the chief conspirator, finally responded in 1995 and 1997 with two public-facing investigative reports that sought to put the events of Roswell to rest.

The Air Force argued that the bodies-wreckage-and-conspiracy narrative intermingled distorted memories with verifiable events, specifically: the discovery of a damaged, high-altitude U.S. military spy balloon, the recovery of crash test dummies parachuted into the New Mexico desert, and two military aircraft accidents.

In the wake of these reports, many of the UFO investigators who had advanced claims of alien debris and bodies either substantially moderated, or fully recanted their claims. For most of those following the saga of Roswell, the crash no longer promised physical proof extraterrestrial visitors to Earth.

…

As indicated by the summary above, Roswell is a big story. For the sake of clarity, we’ve divided that story into three parts:

First, in this article, we will cover the initial incident: the 1947 crash of an aerial object outside of Roswell, New Mexico. In acknowledgment that no account can satisfy all allegations attached to the crash, we will restrict ourselves to the facts as broadly agreed upon by news reports of the time¹, prominent works by UFO investigators², and the investigative reports that the U.S. Air Force produced in 1995³ and 1997⁴. Admittedly, this restriction will result in a substantially pared-down version of the Roswell crash.

Second, in Part 2, we will trace how the nearly forgotten incident gained the attention of a few UFO investigators in the late 1970s and, within a dozen years or so, the public at large. If you’d like to skip to that article, click here.

Finally, in Part 3, we’ll present the case that the U.S. Air Force made in 1995 and 1997 against the bodies-wreckage-and-conspiracy narrative. We’ll also look at the response to these Air Force reports from some of the UFO investigators who played a part in making Roswell perhaps the most famous UAP event (or non-event) in history. Click here for Part 3.

The initial incident

In their barest terms, the events near Roswell, New Mexico, in 1947 were as follows:

A rancher discovered debris and notified authorities. The US Army then recovered that debris, described it to the press as the remains of a “flying disc,” and just as quickly, retracted the statement and said the debris was the remains of a weather balloon.

Near Corona

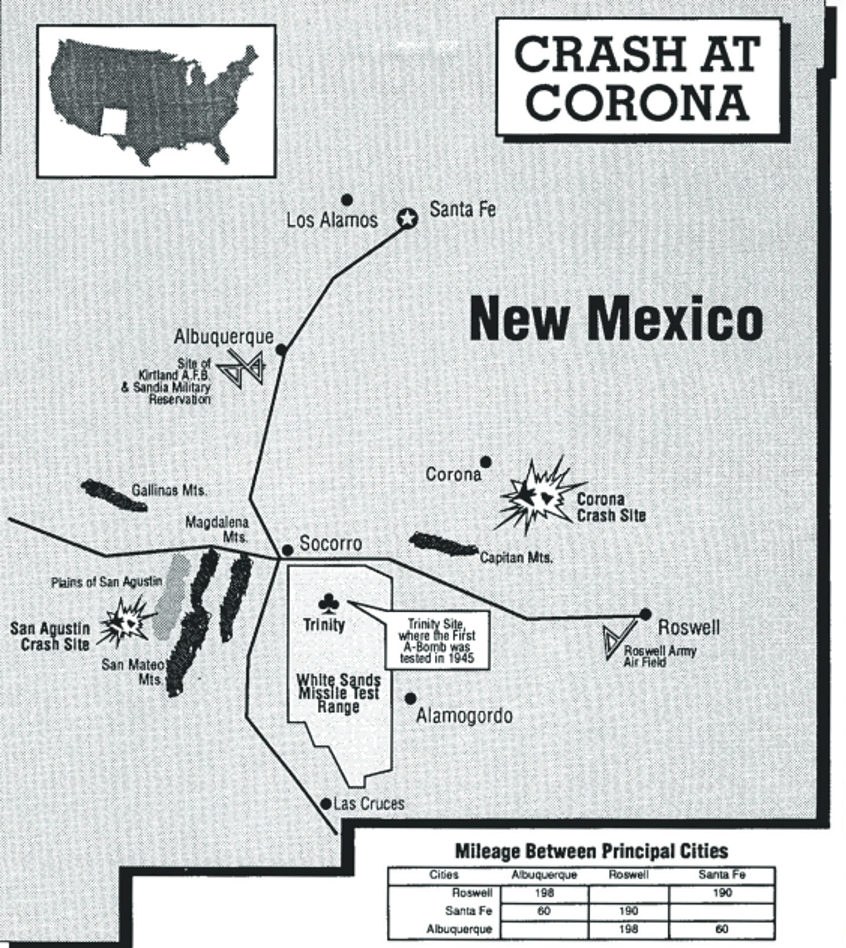

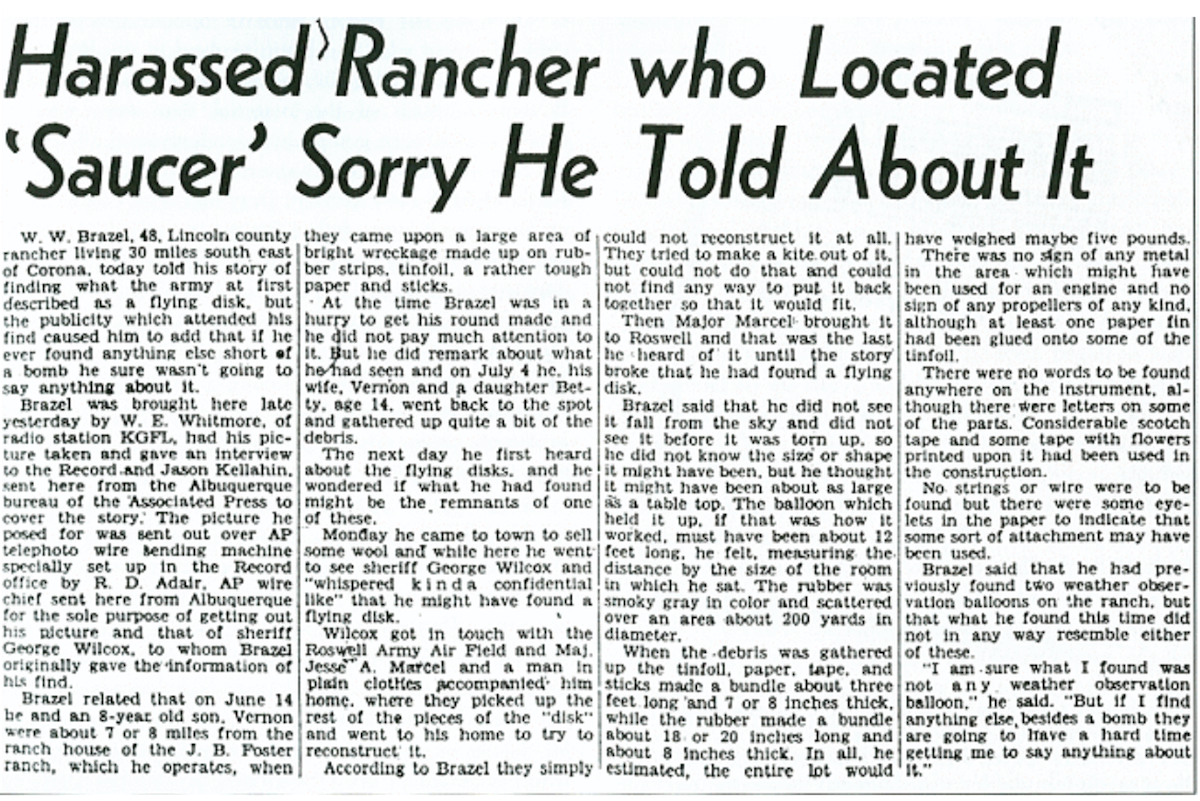

On a day in late June or early July, 1947, W.W. “Mac” Brazel, a sheep and cattle rancher, and his eight-year-old son, Vernon, were minding sheep on their grazing lands near Corona, New Mexico, roughly 75 miles northwest of Roswell, when they discovered debris that appeared to consist of paper, rubber, wood and a lightweight metallic material.

On the morning of July 7, Brazel drove into Roswell for business. While in the city, he informed the local sheriff, George Wilcox, of the debris he had found. Wilcox placed a call to the Roswell Army Air Field (AAF). Major Jesse Marcel, an intelligence officer and member of the 509th Bomb Group of the US Army Air Force, and perhaps one other officer⁵ then accompanied Brazel to the debris site. Marcel left Brazel property with the debris in his vehicle and returned to Roswell Army Air Field.⁶

‘Flying disc’

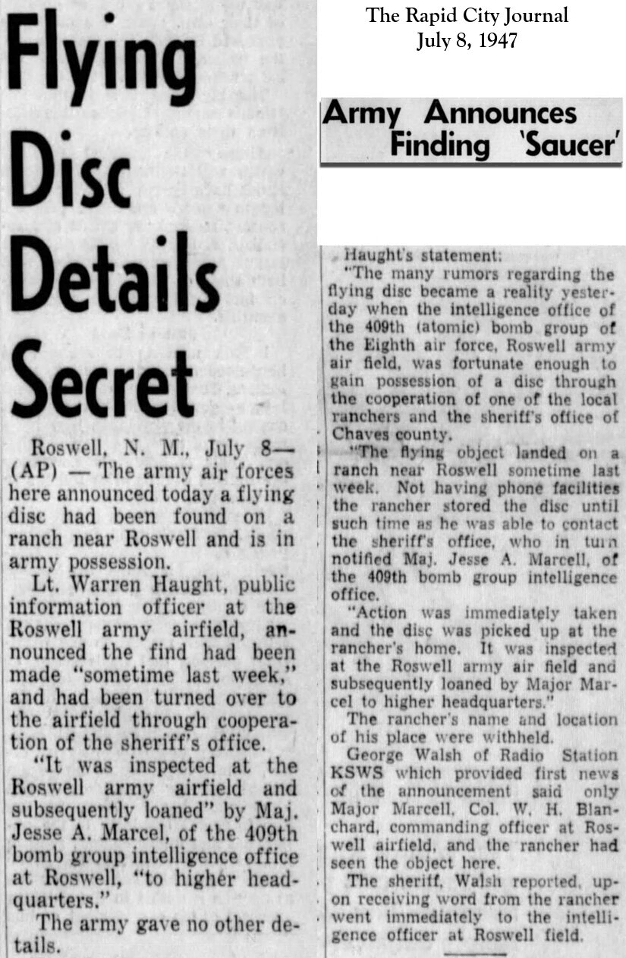

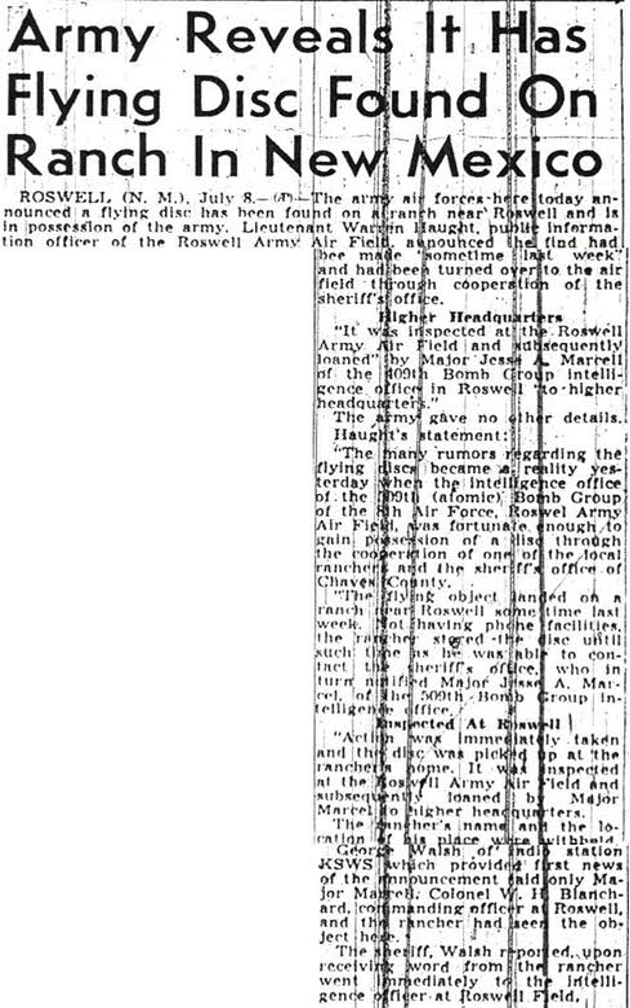

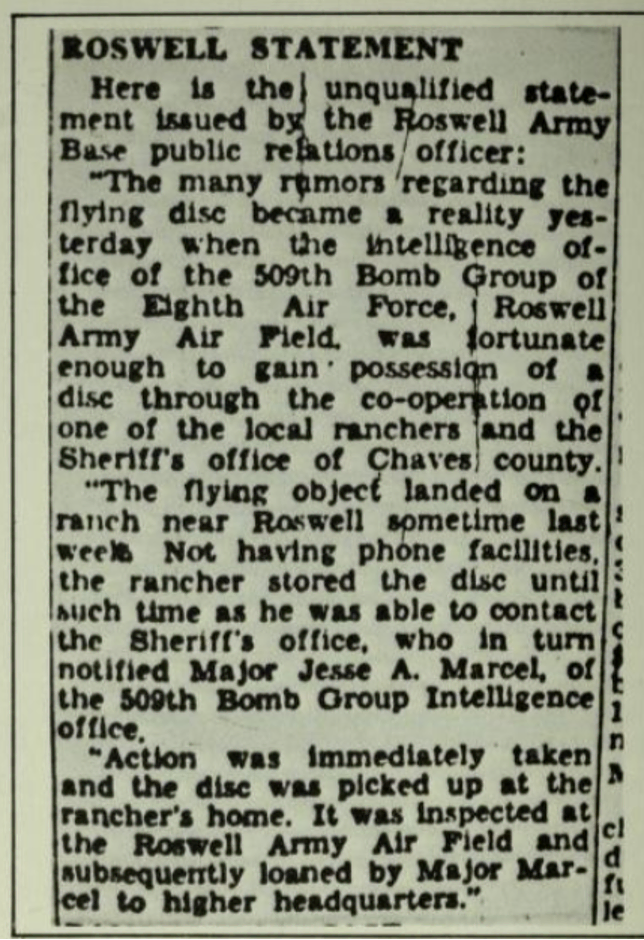

Marcel reported the recovery of the debris to the base commander, Colonel William Blanchard. The base’s duty press officer, First Lieutenant Walter Haut, then wrote up a press release⁷, describing the debris as the remains of a “flying object,” or “flying disc,” that “landed” on Brazel’s land. Blanchard approved the release.

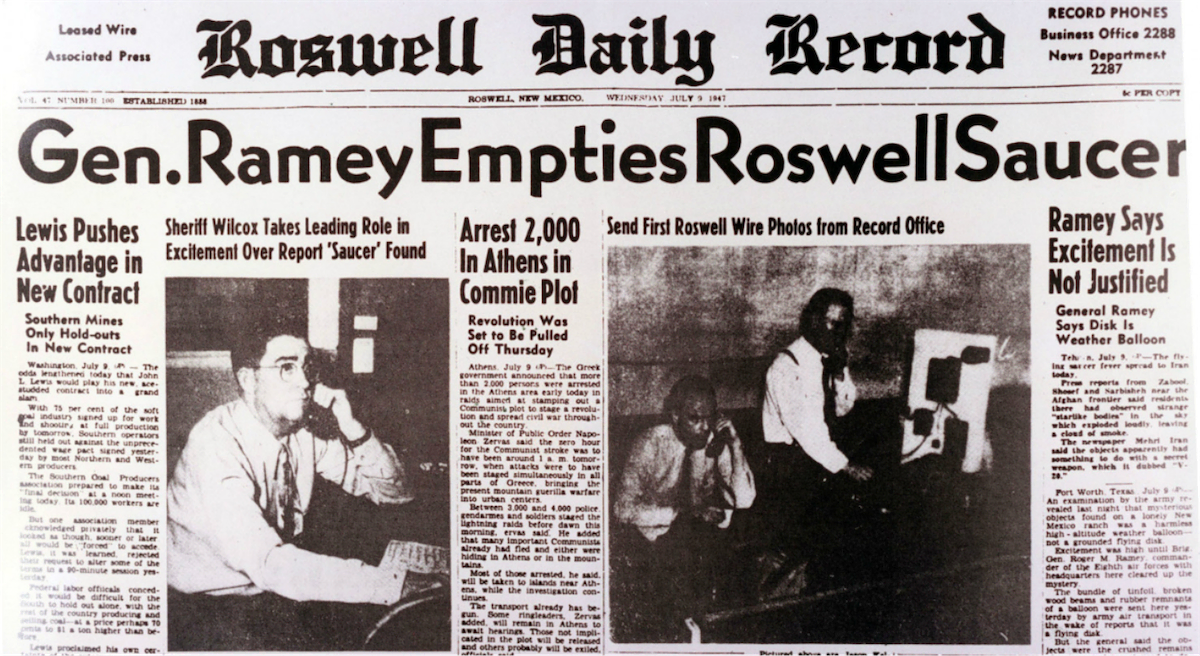

A local radio station, KSWS, was the first to announce the press release, and on the following day, July 8, the Roswell Daily Record printed a front page story under the headline “RAAF Captures Flying Saucer On Ranch in Roswell Region.”

(For readers on July 8, 1947, the term “flying saucer” did not necessarily indicate an extraterrestrial spacecraft. In fact, the term was only two weeks old, first attributed to press reports following a June 24 sighting of nine UAP over Mount Rainier, Washington by a civilian pilot named Kenneth Arnold.)⁷

The Roswell Daily Record story could provide no no detail on the “saucer,” but implied a connection to a July 2 UAP sighting over Roswell by “Mr. and Mrs. Dan Wilmont.”⁸

Additionally, an Associated Press version of the story, closely hewing to Haut’s press release, ran in The Chicago Daily News, The Rapid City Journal, the Sacramento Bee, the Los Angeles Herald Express, the San Francisco Examiner and other AP affiliated news outlets.

Change of course

General Ramey's take

While the “flying disc” headlines were hitting newsstands, Marcel boarded a Boeing B-29 from Roswell AAF with the debris, headed for Wright and Patterson Army Air Fields in Ohio¹⁰, home of Air Materiel Command, the Army Air Force’s intelligence division. However, the plane instead landed at the Army Air Field outside of Fort Worth, Texas, where Brigadier General Roger Ramey and Warrant Officer Irving Newton inspected the material.

According to Ramey, the debris was the remains of a downed high-altitude weather balloon and a crushed “rawin target,” a device that measures wind velocity.

Ramey invited the press to view and take pictures of the debris and that evening he went on local radio to discuss his determination that the wreckage had an earthly origin.

Media Coverage

On July 9, several news outlets, including the Fort Worth Star Telegram, The New York Times, the Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, the San Francisco Chronicle and, of course, the Roswell Daily Record put out stories that followed Ramey’s weather-balloon explanation.

The Roswell Daily Record devoted the most coverage to the debris’ demotion from flying to weather balloon, running the headline “Gen. Ramey Empties Roswell Saucer.”

The paper also featured a story under the headline “Harassed Rancher Who Located ‘Saucer’ Sorry He Told About It,” in which W.W. Brazel is quoted as describing the debris as amounting to five pounds of tinfoil, paper, sticks and rubber that together would have made an object about the size of a “table top.”

“I am sure that what I found was not any weather observation balloon,” Brazel reportedly said. “But if I find anything else besides a bomb,” he added, “they are going to have a hard time getting me to say anything about it.”

With that, interest in the debris discovered near Roswell largely evaporated.

The broader wave

To understand how the Army’s admission of recovering a strange “flying disc” could vanish from public concern, it helps to understand that the event occurred in the midst of the first modern UAP sighting wave.

In the spring and summer of 1947, the UFO phenomena was new, bewildering and surprisingly widespread. By the end of the year, the Army Air Force would receive reports on 243 alleged UAP incidents,¹¹ which likely represents a small fraction of sightings overall.

These alleged sightings stirred a media frenzy, and “flying saucer” news stories proliferated across the U.S.¹² For instance, in the July 9, 1947 New York Times story on Ramey’s weather-balloon explanation, the Times reported recent UAP sightings from Ohio, Iowa, Nebraska, Michigan and Wisconsin, as well as incidents in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and South Africa.

Ultimately, as eye-popping as the events at Roswell may have seemed, they were not especially out of place within the 1947 UAP sighting wave.

Moreover, New Mexico appears to have been a hotbed of sightings at the time. In addition to the Wilmonts’ July 2 sighting over Roswell, UAP were allegedly spotted on June 29 over White Sands, over Albuquerque and Tucumcari on June 30, and again over Albuquerque the following day.¹¹

In fact, according to the Roswell Daily Record, Brazel himself said he would have forgotten the debris he found on the grazing lands if he hadn’t heard talk in town about the “flying disks.”

…

Next up, Roswell, Part II, where we’ll explore how the nearly forgotten incident gained the attention of a few UFO investigators in the late 1970s and, within a dozen years or so, became perhaps the most famous alleged UAP incident in history.