Summary

In July 1947, the U.S. Army recovered a crashed aerial object outside of Roswell, New Mexico. The Army described it to the press as a “flying disc,” and a flurry of news stories ensued. Within hours, however, the Army retracted the statement, now saying that the recovered object was a downed weather balloon, and the incident soon after faded from memory.

That is until UFO researchers rediscovered the crash more than 30 years later. Over the course of the 1980’s and early 1990’s, these investigators made the case that the object had been an extraterrestrial spacecraft, and that its collision into the New Mexico desert had left the corpses of its occupants — aliens — in the possession of the U.S. Government. The government had since hidden evidence of this history-shattering event, the UFO researchers said.

This narrative of bodies, wreckage and conspiracy exploded in the public mind. By the mid-1990’s, many millions of people had consumed it through books, articles, television and film.¹ By one poll, two-thirds of Americans likely believed that an alien spaceship had crashed outside of Roswell some-fifty years ago.²

In 1995 and 1997, after years of dismissing extraterrestrial claims, the U.S. Government through the U.S. Air Force responded with two investigative reports. Roswell was a coverup, the Air Force said, but the coverup of a Cold War spy balloon program. The stories of recovered bodies conflated aliens with parachute test dummies and actual soldiers injured and killed in a pair of aerial accidents, the Air Force said.

By some measure, the Air Force’s investigative reports were successful in settling the controversy around Roswell. For many, over time, some version of events offered by the U.S. Air Force supplanted the extraterrestrial hypothesis as a more likely explanation of the Roswell crash. In fact, some of the prominent UAP researchers who had advanced the narrative of bodies, wreckage and conspiracy have since recanted or substantially downgraded their claims.

For the public, however, Roswell remains synonymous with aliens and conspiracy.

…

As the summary above indicates, Roswell is a big story. So, for the sake of clarity, we’ve divided the topic into three articles.

This article, Roswell, Part 3, will focus on the case that the U.S. Air Force made against the bodies-wreckage-and-conspiracy narrative in its 1995 and 1997 investigative reports. We’ll also look at the impact of that response on the legacy of Roswell as perhaps the most famous UAP event (or non-event) in history.

If you’d like to start at the beginning, click here for Roswell, Part 1, where we attempt to distill, to the extent possible, what diverse sources broadly agree upon as the basic facts and context of the 1947 crash.

If you’d like to trace how the nearly forgotten incident gained the attention of a few UFO investigators in the late 1970s and, within a dozen years or so, the public at large. Click here for Roswell, Part 2.

Schiff’s audit

In January 1994, in response to the massive and sensationalized interest around the Roswell crash, Steven Schiff, member of the U.S. House of Representatives for the first district of New Mexico, formally requested that the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the U.S. Congress’ investigative body, perform an audit of government documents related to the 1947 events at Roswell.

Schiff, who was a member of the House Government Operations Committee, which oversees the GAO, had made individual and ultimately fruitless document requests from the Department of Defense and the National Archives.

"Generally, I'm a skeptic on UFOs and alien beings,” Schiff said to the Washington Post, “but there are indications from the runaround that I got that whatever it was, it wasn't a balloon.”³

In July 1995, the GAO reported that after an 18-month audit of the National Archives, the Army Counterintelligence Corp, the archives of the long-defunct Army Air Force, the U.S. Air Force (the heir to the Army Air Force since September 1947), the U.S. Navy, the National Security Agency, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the National Atomic Museum, the search turned up no documents indicating that the incident near Roswell was anything other than what the Army had represented at the time: the crash of a high altitude balloon in the New Mexico desert.⁴

The audit, of course, did not answer the explosive and widely-believed allegations that the U.S. military had recovered alien bodies from the site, Furthermore, it failed to explain the allegations that the U.S. Government had concealed the truth of the incident. To tackle those controversies, a more thorough response was required.

The Air Force responds

In cooperating with the GAO’s audit, the U.S. Secretary of the Air Force, Dr. Sheila Widnall, ordered a declassification of documents related to the Roswell crash, and following the release of those materials, an investigation into the 1947 incident.⁵

The investigation produced two U.S.A.F. reports, 1995’s The Roswell Report: Fact versus Fiction in the New Mexico Desert and The Roswell Report: Case Closed, released in 1997. The reports, both principally authored by 1st Lieutenant James McAndrew, an intelligence officer of the Air Force Reserve, together amount to over a thousand pages of text, photographs ,maps, charts and other documents in support of the argument that the popular narrative of Roswell was fiction that distorted true events.

It was, the Air Force argued, a radical misinterpretation of …

To the ufologists

Both Fact versus Fiction and Case Closed adopt the stance that to argue point-for-point the extraterrestrial and conspiracy claims advanced by prominent UAP researchers — namely William Moore, Charles Berlitz, Stanton Friedman, Don Berliner, Kevin Randle, Donald Schmitt and others — would be pointless. Instead, the Air Force argues more generally that the alleged conspiracy is impossible:

To suppress the discovery of extraterrestrial bodies and aircraft as alleged by these ufologists would require thousands of soldiers and civilians to nonchalantly maintain total secrecy with no leaks, no disclosure of physical evidence, no paper trail, no Freedom-of-Information-Act slip-ups, or any other security breach for five decades straight despite turnover of personnel and mounting incentives to reveal the “secrets” of Roswell.

No such level of security efficiency has ever existed, the Air Force says.⁶

With that argument in place, the reports moves on to propose what the Roswell crash likely was.

The wreckage — Mogul flight 4

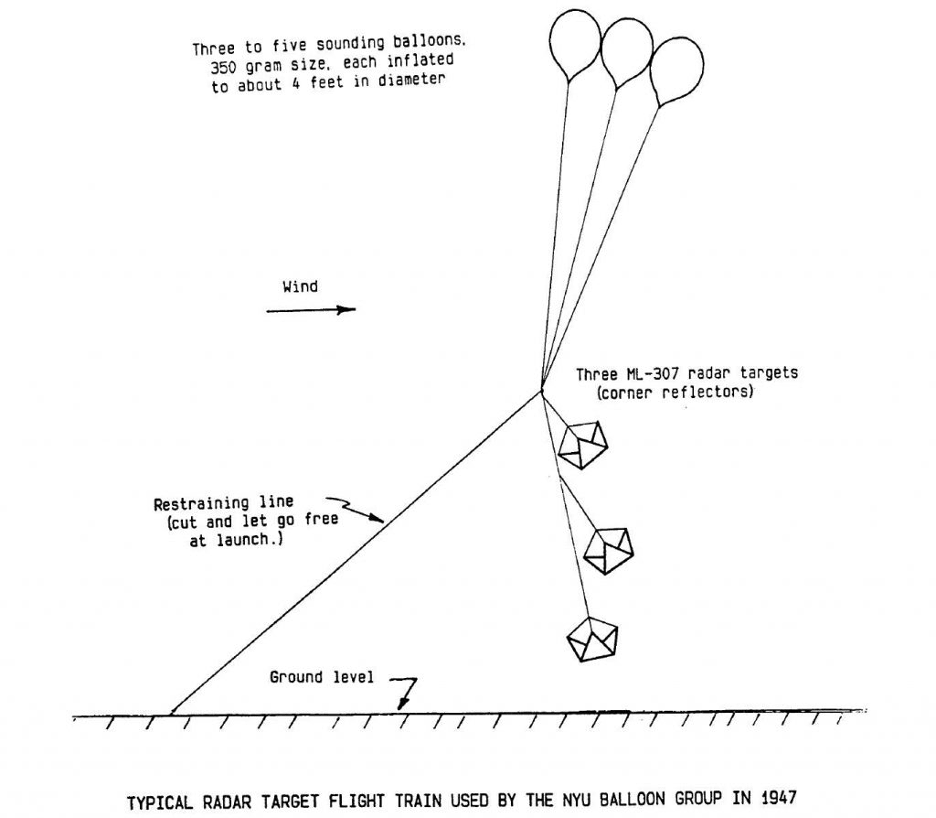

From April through July 1947, the U.S. Army Air Force carried out “Project Mogul,” a top secret operation in which the AAF with research help from New York University, Columbia University and the Air Materiel Command’s Watson Laboratories, an aeronautical logistics group, launched reconnaissance balloons into the upper atmosphere.

The balloons carried “sonobuoys,” cylindrical devices that sent out acoustic signals and measured the resulting echo. The purpose of Mogul was to explore whether such balloon-buoy pairings could monitor Soviet nuclear tests by reading low frequency acoustics in the upper atmosphere.

After two balloon launches in Pennsylvania, Mogul moved to Alamogordo and White Sands, New Mexico. The first two of the New Mexico flights, flights three and four, went missing.

Flight four launched on June 4 from Alamogordo, and according to a diary from Mogul’s field operations director Albert P. Crary⁷, the balloon and its buoy were never recovered by the Mogul team.

Fact versus Fiction argues that W.W. Mac Brazel and his son did not find the wreckage of a flying saucer, but instead found the remains of Mogul flight four.

The Air Force says that debris as described by Brazel, Jesse Marcel and Sheridan Cavitt, a Counter Intelligence Corps officer who was likely with Brazel and Marcel, and as depicted in the photos at General Ramey’s office, matches the components of Mogul flight four: neoprene for the balloon, plastic tubes, a box kite’s wooden frame, the sonobuoy’s aluminum casing and its reflectors.⁸

(Flight three did not have reflectors and so would not be consistent with the debris Brazel found, the Air Force says).

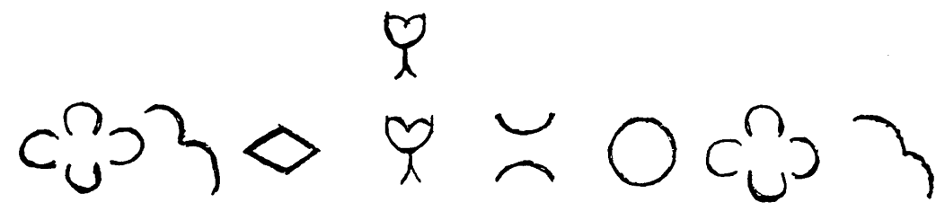

Additionally, numerous witnesses, including Marcel and Irving Newton, the warrant officer who inspected the debris at Ft. Worth AAF, described strange characters, or “hieroglyphics,” on the wreckage. Fact versus Fiction argues that the characters were likely a printed adhesive tape that the Army purchased from a toy manufacturer in order to get around shortages of suitable materials. The tape, which Mogul used to affix the sonobuoy’s reflectors, was pinkish-purple and had geometric floral designs on it, according to Charles B. Moore, the project engineer.

Finally, the shrouded fate of the wreckage is consistent with what would happen to the remains of a top secret reconnaissance device, Fact versus Fiction argues.

Specifically, while the component parts of Mogul — balloon, sonobuoy — were mundane items, the fact that high altitude Army balloons were carrying sonobuoys was classified along with the aims of research.

Project engineer Charles Moore, for instance, was unaware that he was designing devices to monitor Soviet nuclear technology. The Air Force argues that the fact that officers Jesse Marcel, Sheridan Cavitt, and William Blanchard did not know of Mogul, despite their access to military intelligence, is entirely consistent with the project’s compartmentalized, need-to-know structure.

In fact, Fact versus Fiction argues, no one knew specifically what the debris was until it passed from Roswell to Ft. Worth to Wright Patterson in Ohio, where it came before an Air Materiel Command officer named Marcellus Duffy. Duffy, who was aware of Mogul, called Colonel Albert C. Trakowski, who in 1947 was a Captain and Mogul’s project officer. Trakowski affirmed that the wreckage was from a missing Mogul flight.⁹

The bodies — High Dive

Whereas Fact versus Fiction offered an explanation for the initial incident near Roswell, 1997’s Case Closed offered an explanation for the stories of bodies recovered from the desert.

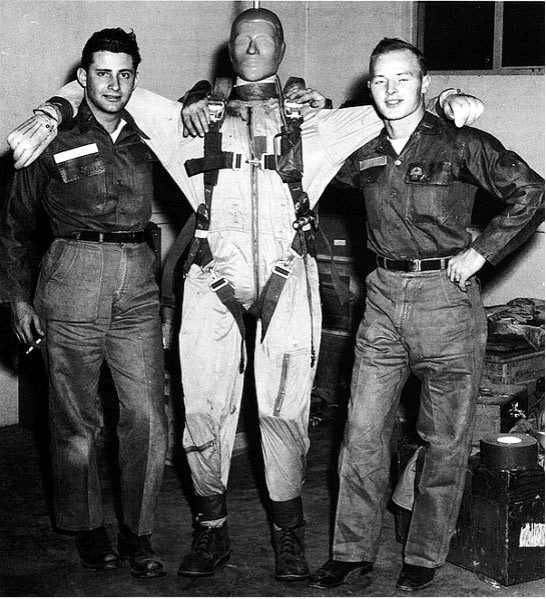

From 1950 onward, the Air Force used “anthropomorphic dummies,” more commonly known as crash test dummies, in research balloons over New Mexico. The dummies, which were embedded with a variety of instruments, gathered data on the effect the high altitudes would likely have in human physiology.¹⁰ In 1953, the Air Force started dropping the dummies from the sky.

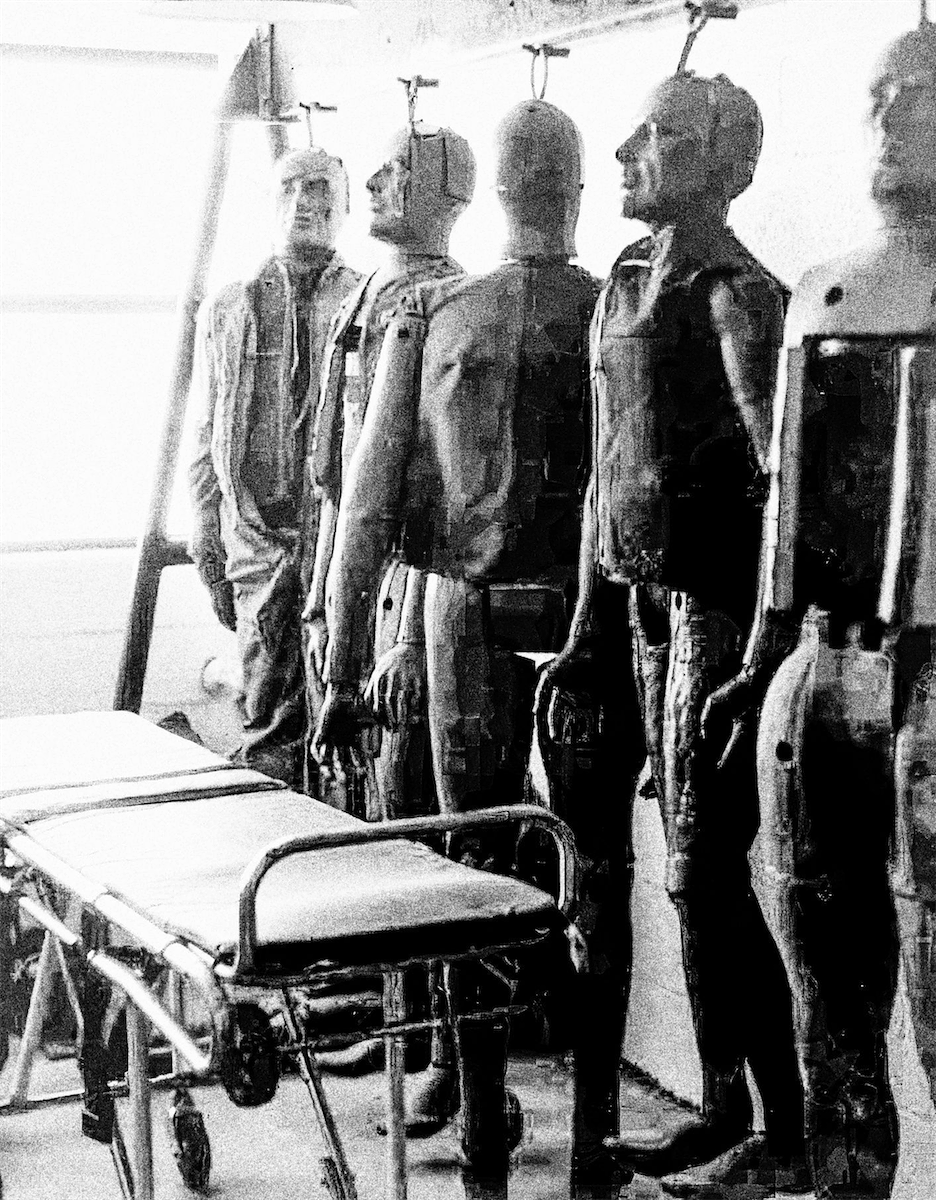

The Air Force’s first iteration of high-altitude “dummy drops” over New Mexico was “Operation High Dive,” a project intended to devise a method of returning pilots and even astronauts to earth with parachutes. From 1953 to 1959, the Air Force ran approximately 50 tests dropping a total of roughly 100 dummies from altitudes as high as 98,000 feet.¹¹

The dummies wore one-piece, silvery suits, were “bald,” and throughout the tests suffered damage that included burns, scrapes, and lost fingers, limbs and heads.¹²

Many of the dummies, pulled by winds, fell outside of their targets at Roswell and White Sands, which necessitated Air Force recovery teams to search them out. The teams consisted of eight to twelve personnel, often driving M-35 cargo trucks, often called “wreckers” or a “six-by-six”.¹³

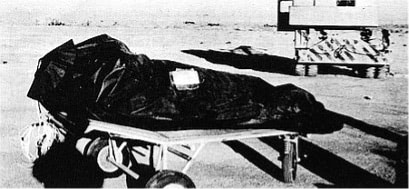

Upon locating the dummies, the teams would often load them into insulated “body bags” to safeguard the embedded instruments for changes in temperature. Recovery teams transported the dummies on gurneys and packed them in coffin-like crates.¹⁴

Case Closed argues that these dummy drop recoveries satisfy many of the body-and-wreckage accounts. By and large, those accounts allege that witnesses came across downed aerial objects and bodies. The bodies are often described as bald and dressed in one-piece suits. A few accounts mention the beings having four fingers. The witnesses describe that military personnel arrived in trucks matching the description of “wreckers” and that they commenced recovery, placing the beings into body bags and coffins and then into the trucks.

Case Closed also takes pains to argue that the versions put forward by Randle, Schmitt, Friedman and Berliner unduly selected evidence from the witnesses to confirm the Roswell-spaceship hypothesis.

In early interviews, witnesses often could not remember a date. The Maltaises, for instance, said “around 1950.” Only later were these vague accounts harmonized to the 1947 incident, Case Closed argues.

Additionally, Case Closed says, ufologists ignored witness statements that supported a non-extraterrestrial explanation. For example, James Ragsdale explicitly said, “They was using dummies in those damned things.”¹⁵ Gerald Anderson, who allegedly discovered the San Augustin crash site, said “I thought they were plastic dolls. I didn’t think they were real.”¹⁶

The Air Force on Dennis

Excelsior and the crash

Having offered a non-ET account for the bodies-and-wreckage, Case Closed moves on to explain the account of one Roswell’s most influential witnesses: Glenn Dennis, the mortician.

Case Closed says that Dennis’ various accounts all together allege the following:¹⁷

He was contacted about specialized caskets and how to handle bodies exposed to the elements.

He saw an vehicle parked in the rear of the hospital containing wreckage that looked like the bottom of a canoe

He noticed a heightened state of security and was warned away by a “redheaded captain” or a “big redheaded colonel.”

He listened to a nurse describe “very mangled,” “black,” “little bodies,” with “swollen heads” and that gave off a strong “odor” and that the bodies were placed in “body bags.”

Dennis’ story, Case Closed argues, is likely the merging of two incidents.

First, in June 1956, a Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter fueling airplane accident burst into flames shortly after takeoff from Walker Air Force Base (formerly Roswell AAF) when a propellor punctured a fuel tank.

All 11 crewmen died, and the airplane crashed approximately nine miles south of the base. Recovery teams brought the bodies to the hospital at Walker AFB for identification. All of the bodies were mangled and blackened by flames. Some were missing legs and had suffered head trauma. The bodies, sodden with fuel, gave off an overpowering stench.¹⁸ Records indicate that Ballard Funeral Home, Dennis’ employer, assisted in performing autopsies.

If Dennis worked with the fallout of the Stratofreighter crash, he likely would have come into contact with Colonel Lee Ferrell, the commander of Walker AFM Hospital. Ferrell was six-foot-one, five inches taller than the average US male at the time,¹⁹ and he had red hair.²⁰

According to policy, until the bodies were identified, no civilian or military personnel could release information on the incident.²¹

According to Case Closed, the second incident Dennis likely conflated into his account was a May 1959 balloon crash.

The crash was part of “Project Excelsior,” an heir to Operation High Dive in that it explored the effects of high altitude on human physiology. Unlike High Dive, however, Excelsior moved from dummies to manned missions in which pilots executed parachute jumps from the stratosphere. Excelsior boasted a successful track record of jumps, including the record highest parachute jump until 2012, however, it suffered a substantial training mishap on May 21, 1959.

On that day, a three man Excelsior-crew forced their balloon into an urgent landing 10 miles north of Roswell to avoid oncoming inclement weather. As the balloon’s gondola touched down, it threw the men, and trapped one beneath, crushing his helmet and delivering severe head trauma. That pilot, Captain Dan D. Fulgham, was rushed to Walker AFB Hospital.

Meanwhile, Excelsior personnel gathered the gondola and balloon and drove to Walker AFB Hospital to check on Fulgham.²²

Fulgham’s head had swollen grotesquely. According to Captain Joe Kittinger, one of the three Excelsior pilots, Fulgham’s “whole face had swollen up and his nose barely protruded.“²³

However, Fulgham did not require an overnight stay at Walker. On hearing this, Kittinger wanted to get his crew out of the hospital to avoid questions from Walker AFB flying safety officials.

According to Kittinger, when he later brought Fulgham to see his wife, she allegedly asked, “Where’s my husband?”

“Ma’am, this is your husband,” Kittinger recalled saying. “I presented her this blob that I was leading down the ramp. And she let out this scream you could hear a mile away.”²⁴

Had Dennis been at Walker AFB hospital, as he often was, he likely would have seen a military vehicle by the emergency entrance carrying an Excelsior balloon gondola, not unlike the bottom of a canoe.²⁵ Furthermore, he may have received a story connecting a downed object with the tale of a grotesquely large head. Finally, he could have encountered Kittinger, who was a “redheaded captain” and was eager to avoid word getting out about the incident.

Time and distortion

Of course, for Dennis to have conflated the Excelsior mishap and the Stratofreighter crash into his memories of the 1947 Roswell crash requires that he merged events that took place over a decade apart.

Case Closed argues, however, that Dennis did just that and that his account shows evidence of confusion over the chronology of events and a tendency to remember different people as a single individual .

For instance, Dennis recalled an African American sergeant with the redheaded officer, which would be unlikely given that the military was racially segregated in 1947.

Additionally, Dennis said that aside from his nurse friend, he spoke with a nurse Captain “Slatts” Wilson. According to the personnel records of Roswell AAF and Walker AFB, the hospital did have a nurse captain named Lucille Slattery, who went by “Slatts”, but she did not come onto base until after the Roswell crash. Moreover, the only nurse “Wilson” in the records was an Idabelle Wilson who began at Walker AFB in 1956.²⁷

Larger gaps appear in regard to Dennis’ friend, the nurse at Roswell AAF who was allegedly distraught from witnessing the autopsy of three alien corpses. Dennis did not initially share her name, but later named her as “Naomi Maria Self.” According to Case Closed, no record of such a person at Roswell AAF or Walker AFB exists. Additionally, Dennis repeatedly said that she died in a plane accident, perhaps in transfer to the U.K., but later asserted that she became a nun.²⁸

Case Closed does not accuse Dennis of any intentional misrepresentation. Instead, it suggests that his account was distorted by time and the lure of an extraterrestrial narrative.

Dennis first relayed his story to Stanton Friedman in 1989, 42 years after the events at Roswell. Moreover, he relayed it soon after watching a vivid depiction of an alien crash on Unsolved Mysteries.

In the next few years, Randle, Schmitt and many other ufologists would ask him time and again for more details. Meanwhile, more extreme Roswell theories circulated, the alien tourism in his hometown grew, and media hype escalated.

Under these circumstances, Case Closed argues, Dennis and other witnesses played a perhaps unwitting part in a large-scale distortion of the truth. They relayed verifiable incidents — Mogul flight four, dummies drops and recoveries, the Stratofreighter casualties and more — at the remove of decades to interviewers predisposed to hear a tale of extraterrestrials and conspiracy.

“The incomplete and inaccurate intermingling of these actual events were grounded in just enough fact to weave a sensational story,” Case Closed concludes, “but cannot withstand close scrutiny when compared to official records.”

Roswell fades, but persists

The U.S. Air Force did not arrive at its conclusions alone. A year before the first report, Fact vs. Fiction, Karl Pflock, a UFO researcher, former deputy assistant secretary of defense and intelligence officer, concluded that Project Mogul produced the debris that W.W. “Mac” Brazel found in his grazing lands in 1947.²⁹

By his account, Pflock went to Roswell in the early-1990’s with the hope that the mystery would yield proof of extraterrestrials. Instead, he found no hard evidence and little documentation, but a multitude of diverging accounts, most secondhand and at best recorded three decades after the events. Worse, the accounts were taken in an increasingly carnival-like atmosphere in which the presence of extraterrestrials and a government conspiracy was a forgone and often profitable conclusion, Pflock says.

The problem, according to Pflock, is that the more publicized a UAP incident is, the more misinformation surfaces, intentional or not, muddying the waters and obscuring an investigator’s view of the truth.³⁰

To greater and lesser degrees, a number of the UAP investigators who advanced the bodies-wreckage-and-conspiracy narrative came around to Pflock’s take on the hype of Roswell.

William Moore, who co-authored the first book on the Roswell crash and who performed with Stanton Friedman the first comprehensive investigation of the case, wrote to the UFO writer James Mosely in 1997 that “after deep and careful consideration of recent developments concerning Roswell … I no longer am of the opinion that the extraterrestrial explanation is the best explanation for this event.”³¹

Kevin Randle, perhaps once the most ardent proponent of the bodies-wreckage-and-conspiracy narrative, has likewise stepped back from the extraterrestrial theory of Roswell. For years, Randle vigorously rebutted the Air Force’s case in a series of books and articles. More recently, however, Randle has modified his stance, saying that Roswell is not “the robust case I had once believed it was.”

In the end, Randle says, Roswell is “a multiple witness case without sufficient documentation and without any sort of physical evidence.”

He adds, “At one time I would have told you it was alien. Today I tell you that I just don’t know.”³²

Unlike Moore and Randle, Friedman never revised his take on Roswell.³³ Friedman died in 2019.³⁴

For its part, the American public reflects this mix of shifting and implacable views. In June 2022, near the 75th anniversary of the Roswell crash, Fairleigh Dickinson University asked poll respondents whether it’s plausible that extraterrestrials crash-landed in the New Mexico desert all those years ago. One out of three said yes.³⁵

While twice as many respondents replied yes to substantially the same question in 1997 at the fiftieth anniversary³⁶, the persistence of Roswell’s connection to extraterrestrials and government conspiracy likely reflects that Roswell, for all its strengths and weaknesses as a case, has entered a canon of American mythology.